ACE Projects Illuminated: Reflecting on the Success of the PETES ACE Project

Two years ago, the Hull sector of Gatineau, Quebec experienced a devastating flood. A year later, a tornado swept through the region. At the beginning of the school year, project coordinators in schools participating in Arts, Community and Education (ACE) Initiative were asked to identify a theme that would bring the school and community together through an artistic learning experience. When Pierre Elliot Trudeau Elementary School’s (PETES) coordinator, teacher Fiona Medley was considering the theme for the school’s ACE project, water felt like a natural fit. In consultation with other grade three teachers, all expressed an interest in encouraging thoughtful reflection on the positive relationship of water to the community. The artistic modality for the project also felt obvious to Fiona; she herself comes from a music background and saw music education as lacking at PETES. She noted that “the main point of the project was to bring quality music educators that we have in our community into our school”.

Photo credit: Fiona Medley

The ACE Artists chosen for the project were percussionist Leo Brooks and choral director Tim Piper, both well-known in the capital region for providing quality youth music programs. Fiona stated that inviting two male musicians was deliberate, to help dismantle gendered ideas of who can participate in music production. They decided together to ground the theme of water in a text, to support the integration of the theme in students’ English Language Arts and French Second Language learning. They selected the book Water’s Children by Quebecois author Angèle Delaunois, which explores the perspectives of twelve children from around the world on the significance of water to their communities. The diverse insights of the characters were also reflected in the varied sources from which knowledge was pooled to think through the importance of water. Indigenous community partners, the Ottawa River Keepers, were invited in to educate on the importance of water to the local environment, while the local non-profit Enviro Édu-Action taught students about the urban water cycle.

As the vision for the project developed, the planning team decided that it would be interesting to create a play based on the book at the end of the project, which in Fiona’s words, would “celebrate the best practices emerging from our knowledge of music, water and diversity”. The collaboration and shared critical thinking both witnessed in Water’s Children and by the variety of experts brought in to teach on the value of water was integral to the creation of the play, as the students were invited to participate in the play’s creative process by singing parts of the script in their mother tongues.

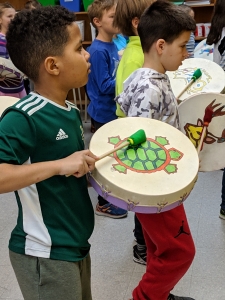

Leo and Tim worked regularly with students over three months. To teach rhythm, Leo used Djembe drums purchased by the school. He taught a non-Western system of associating words and phrases to rhythm, because, he states, “it makes a more dynamic connection with the kids”, noting that it helped the students reflect on how “different words and sounds have different emphasis”. The students were then also encouraged to create movement based on the words and rhythms, a form of experiential learning that Fiona notes is “linked to the sense of play, of interpretation that is found in creation and analysis in language”. Tim based his teaching in a more Western form of music literacy, teaching musical notation to help the students strengthen their singing skills.

Both Leo and Tim noticed that the students have developed their musical skills over their residencies. Leo states that when he first arrived, “some of them couldn’t hold a beat if it was in a box, but now they are really solid”. Tim remarks on how important time has been for the development of these skills. He states that “you need to give it time to see progress. You also need trust. When we first started producing songs, there was a lot of mistrust. Now that the students and educators have put in the time, they’ve realized that it has value”. All three have observed a shift in the school in valuing artistic creation because of the long-term nature of the project and the dynamism of the teaching; Fiona notes that there’s been “buy-in” of both students and educators into the project that she believes will last beyond the projects closure. She also reports that the community partners have been more involved at the school since the project began.

Photo credit: Fiona Medley

“Water is Life” premiered on April 5th at PETES School. The performance began with PETES Indigenous Cultural Aide, Mariah Smith Chabot singing a water-honouring song with some students. The key refrain in the play and in the book, “water is life”, was developed into an anthem which was sung in English, French, Cree and Algonquin. The community was welcomed to watch the production, culminating the ongoing effort in collective reflection and appreciation by extending these acts beyond the school to Gatineau at large. 250+ community members attended the evening performance, and five parents lent their support volunteering throughout the performance. Although the Mayor of Gatineau, Maxime Pedneaud-Jobin, though unable to attend the performance, sent a thoughtful letter to the students which was included in the program. The Honourable Catherine McKenna, Minister of the Environment and Climate Change, also sent her regrets for being unable to attend the show, and sent good wishes and applause for the efforts of the students to raise awareness on environmental issues.

Tim notes that the “process has been excellent”, a statement which is clearly demonstrated in the thought and care that Fiona, Leo and Tim gave to the project. Teachers reported that for the 87 Grade three students involved, student engagement in learning and advancement in individual learning was described as the highest that the they had witnessed during the school year, and fifteen students with different needs were described as having been most positively affected by the experience. Moreover, through only the grade three students performed, all 550 students in the school explored the water theme in their classrooms in some capacity, and three senior classes helped to decorate the gym. School pride was evident in the teachers’ and students’ reactions. The positive outcomes of this collaboration have compelled the principal of PETES to say that he will be ensuring that artist residency projects that benefit the school and community will take place annually in the school. The MNA, School Board Chair and Director of Education all attended the daytime performance and expressed their intention to support PETES and other Western Quebec schools in integrating artists to achieve student learning outcomes, particularly for students with different needs.

Tim, Leo and Fiona note the key partners that have enabled them to realize this project, including the ELAN Quebec’s ACE Initiative, the Culture in the Schools Program, the Community Health and Social Services Network and their school’s own fundraising efforts. They also express gratitude for the support from the Ottawa River Keepers and Enviro Edu-Action organizations, both of whom have become stronger partners through the project. The resourcefulness of the trio in seeking and drawing upon excellence in their community to encourage critical reflection on the importance of valuing the dynamism of their environment and people led to a poignant and healing final performance. Everyone can participate in and benefit from nurturing the water cycle, and the communities it feeds, just as everyone can participate in and benefit from musical production.

Photo credit: Christie Huff