Organization Spotlight – Teesri Duniya Theatre

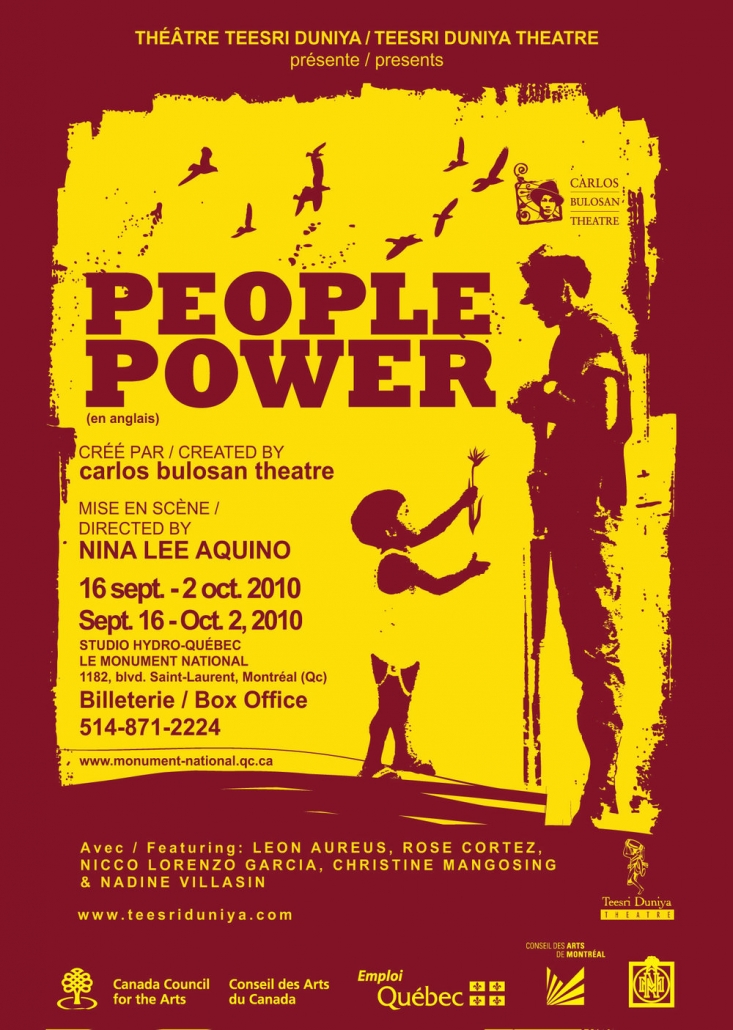

Founded in 1981 by Rahul Varma and Rana Bose, Teesri Duniya Theatre is one of the very few culturally-inclusive companies in Canada. It is also one of its kind in Quebec due to our production of plays by visible minorities, First Nations, as well as dominant cultures. 95% of Teesri Duniya’s productions are groundbreaking premiers directed by leading directors, including India’s iconic director Lt. Habib Tanvir. Teesri Duniya is proud of the fact that most of the theatre’s directors are women. Productions range from “Counter Offence”, GG winner “Reading Hebron” (1990s), “My Name is Rachel Corrie”, and GG-winning First Nations play “Where the Blood Mixes” (2012) to dance-theatre such as “The Encounters” and international hits like “Bhopal” and “State of Denial”. Teesri Duniya is also proud to have launched the careers of many visible minority artists and playwrights. New plays and playwrights are at the heart of Teesri’s vision. Teesri Duniya exists to produce bold, groundbreaking and culturally diverse plays that provoke conversation.

Teesri Duniya was founded in 1981. Can you talk a bit about the founding of the theatre company, what inspired its first steps? What were some of the initial steps and approaches you took during the first few years of Teesri Duniya? Some of the very first performances?

Teesri Duniya was founded in 1981. Can you talk a bit about the founding of the theatre company, what inspired its first steps? What were some of the initial steps and approaches you took during the first few years of Teesri Duniya? Some of the very first performances?

Teesri Duniya was founded to fill a representational gap in Canadian theatre. When I first arrived here in 1976, there was a notable absence of stories of people of colour. There was a lack of politically-driven plays and Canadian theatre operated within a monochromatic, bicultural hegemony. Teesri Duniya sought to represent what Canada truly was: a nation consisting of Indigenous people, diverse cultures, many languages, diverse histories and multiple heritages. It was formed to tell stories of marginalized communities and raise issues ignored by the dominant national theatre.

In its initial years, Teesri produced a series of contemporary Indian plays as well as some of my original plays – all of which were in Hindi. Our very first play was Badal Sircar’s Julus in 1981, a new-wave Hindi play about hope against despair. Three years later, we produced our first English play, The Great Celestial Cow by Sue Townsend; the success of this inspired me to begin writing and directing my own plays in English. For the first fifteen years of playwriting, I didn’t qualify for arts funding. However, things changed and in the mid-nineties I was declared eligible for arts funding; with the funding came the opportunity for Teesri to produce plays of a more professional standard.

Has anything about the mandate or approach to projects, changed over the past few years, or adapted to new contexts?

At Teesri’s inception, our understanding of cultural diversity was rooted in the countries we came from, the countries we left behind. Over time, this understanding developed to include a more comprehensive view of cultural diversity that was rooted more firmly in the local context. We presented and engaged with diverse global themes while maintaining local significance. We wanted our projects to be relatable, relevant and thought-provoking.

Apart from this nuance that evolved during our initial years, the company’s mandate has remained constant: producing socially and politically relevant theatre that supports a multicultural vision and promotes intercultural relations. From its founding, Teesri Duniya has been committed to multi-ethnic as opposed to color-blind casting. We seek to embody diversity through our actors and directors rather than merely representing it.

Teesri Duniya has helped launch the careers for a large number of visible minority artists and playwrights. Can you mention a few of the success stories?

Teesri has not only contributed to the development of several artists of colour, but we have also purposefully created the conditions necessary for them to succeed in the field by creating works written for them.

We have showcased the talents of numerous artists of colour who are rarely given the opportunity to act in mainstream productions, including Tova Roy, Shalini Lal, Prasun Lala, Anurag Dhir, Amena Ahmad, Maya Dhawan, Ranjana Jha, and Aparna Sindhoor of South-Asian descent; Emilee Veluz, Cecile Cristobal, Elizabeth LaFranco and Carolyn-Fe Trinidad, of Asian descent.

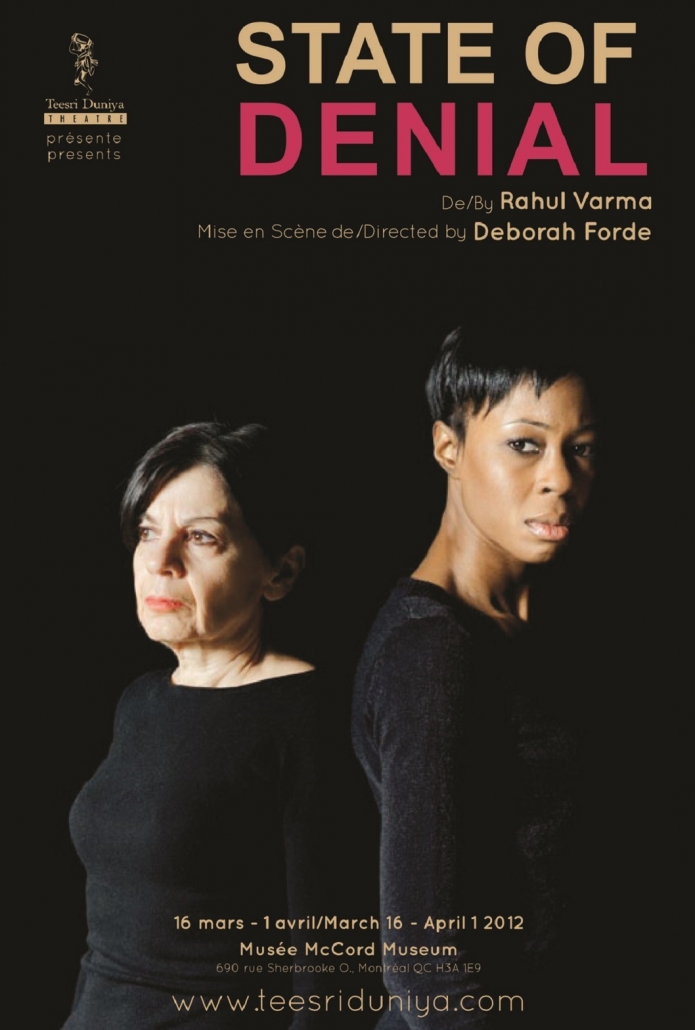

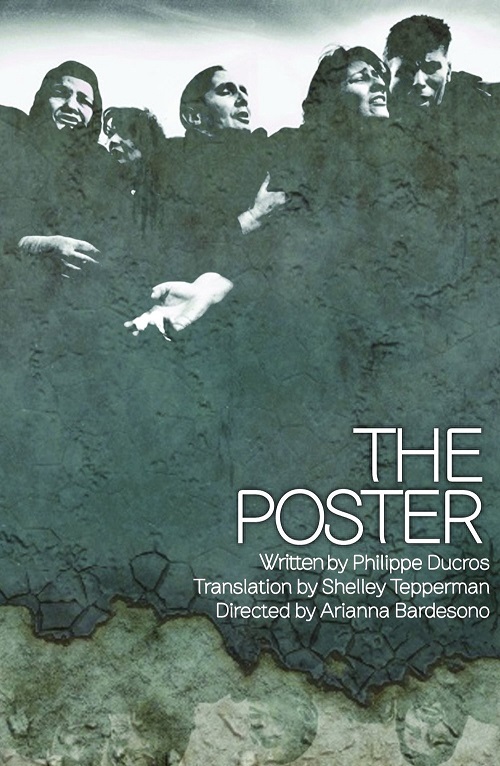

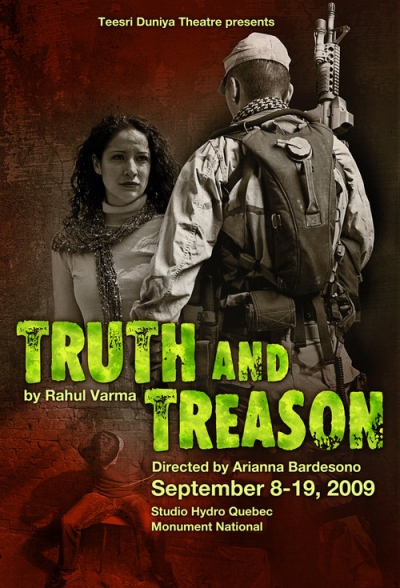

Arab-Canadian actor Abdel Abdelgafour Elaaziz played his first lead role in English in play Truth and Treason (2009); since then he has acted in many plays and films both in French and English. Actor Mohsen El Gharbi made his English language debut in our play The Poster, and has since performed both in English and French as well as created his own new plays. Natalie Tannous, an Arab-Canadian actress, launched her career in State of Denial, and has been a busy actress performing and traveling across the country since then.

Filipino-Canadian actress Emilee Veluz, got to play a character of her own culture in Teesri’s production of Miss Orient(ed) for which she won the best actress award. She has been busy since. Similarly, since performing for the first time in Miss Orient(ed), Carolyn Fe-Trinidad has formed her own production company called AltaVista Productions which has over 5 productions to date, has won awards, done commercials, and acted on big stages.

In addition, we presented directors Arianna Bardessono and Deborah Forde with directorial debuts with Truth and Treason and State of Denial respectively. Bardessono won the John Hirsh prize and Deborah Forde has directed many plays since in addition to mentoring young artists.

Many of the plays produced by Teesri Duniya are informed by themes of conflict, war, militarization, colonialism and displacement (example, the confrontation with political oppression and Israeli occupation of Palestine in “Birthmark”). Identities and the common threads of humanity can easily become subsumed in military-state apparatuses, tipping over into a brute nationalism. Can you reflect on the ways in which these themes manifest in your work and research?

Many of the plays produced by Teesri Duniya are informed by themes of conflict, war, militarization, colonialism and displacement (example, the confrontation with political oppression and Israeli occupation of Palestine in “Birthmark”). Identities and the common threads of humanity can easily become subsumed in military-state apparatuses, tipping over into a brute nationalism. Can you reflect on the ways in which these themes manifest in your work and research?

Although my plays are fiction, they always reflect real socio-political contexts, drawing upon themes that ring true in our society. The themes you mention manifest most prominently in Truth and Treason.

Truth and Treason is set in 2007 during the American occupation of Iraq; it’s set in a time when human tragedy is drowned out by militarism, Islamic fundamentalism, and warring political factions. The play unfolds around a young girl, Ghazal, who is killed in search of her father – an Iraqi writer imprisoned under Saddam’s regime. The tragedy of her death plays out on several levels. Ghazal is shot at a checkpoint for the Conference for Democracy and the Salvation of Iraq at the hands of an American soldier. The officers discover she has a rare blood type and requires an immediate transfusion from her father in order to be saved. Deliberations on how to proceed end with the commander overruling any transfusion from the girl’s ‘terrorist’ father. Chaos ensues on the political level, directed by those who would exploit, dismiss or deny the death of Ghazal, all in the name of combating evil. Meanwhile, Ghazal’s parents navigate their own whirlwind of grief, revenge, and forgiveness.

Through the course of the play, we see the conflicts that arise between duty and conscience, the conflating of the personal with the national, and the true nature of ‘war’ and ‘terror’. It seeks to question where and by whom the real ‘war on terror’ is fought.

Is there anything you would like to mention now, in retrospect, about some of your previous projects like El Hotel de los Refugiados, Bhopal, State of Denial, or others?

Each of these plays were produced with the objective of responding to human conditions and social and political discords. They were a form of creative dissent in a world where dissent is the only means of tackling an oppressive authority. Authoritative regimes and weapons of mass destruction do not exist in isolation halfway across the world. They are living reminders of man’s inhumanity against man, of the denial of social justice, the suppression of civil liberties, and the increase of control and state repression in the pursuit of global supremacy. These social and political injustices affect the well-being of society and as result, theatre must take up a pacifist humanitarian war. These projects are Teesri’s war to build a better world, to uphold peace, human dignity, and positive values through the creative analysis of our political order.

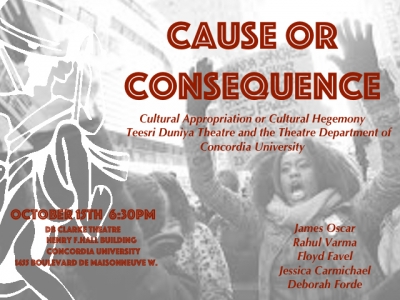

Your work has helped extend dialogues on “local” (Montreal) issues of inclusion, diversity, equity, and cultural appropriation. For example, the New York Times reported on the “Cause or Consequence: Cultural Appropriation or Cultural Hegemony” post-SLAV talk (organized and presented by Rahul Varma and Deborah Forde). Can you reflect on this effect of expanding discourse, and connecting Montreal / Quebec issues with larger conversations?

Your work has helped extend dialogues on “local” (Montreal) issues of inclusion, diversity, equity, and cultural appropriation. For example, the New York Times reported on the “Cause or Consequence: Cultural Appropriation or Cultural Hegemony” post-SLAV talk (organized and presented by Rahul Varma and Deborah Forde). Can you reflect on this effect of expanding discourse, and connecting Montreal / Quebec issues with larger conversations?

The issue raised by the production of SLAV speaks to the larger issues of cultural hegemony, cultural appropriation and marginalization of historically oppressed communities. Lepage’s production of a theatrical odyssey centred on the songs of African-American slaves and forced labourers is not problematic because it attempts to explore the stories and histories of a different culture, but rather because it distorts and exploits colonial histories. Cultural freedom is sacred, but that does not condone the production of a show about black slavery without the equitable participation of black people. Moreover, to use the defence of colour-blind casting is to blatantly ignore a history of oppressor and oppressed that is entrenched in colour-based discrimination.

Certainly, SLAV sparked the conversation on these issues, but they have existed for quite some time now. In 2014, we saw Théâtre du Rideau Vert’s (TRV) year-end show Revue et Corrigée attempt to satirize Quebec personalities by putting on a blackface performance. Most theatre companies practice color-blind casting, which by itself isn’t problematic necessarily, however it does become an issue when it infringes on the ethics of cultural representation.

These instances of cultural appropriation are closely tied to the cultural politics of Quebec which favours the assimilation of minority cultures into the dominant culture as opposed to a more egalitarian multiculturalism. The result is a disproportionate access to resources and representation for artists of colour.

Although the issue of a cultural hegemony is more pronounced in Quebec, it is by no means unique to it. We saw a similar debate arise from The Royal Shakespeare Company’s production of The Orphan of Zhao. It is crucial that we expand discourse on these issues to tackle the very real implications that a production like SLAV has on Canadian society in order to build a space that is truly inclusive of all cultures.

Can you talk about some of the ways in which Teesri Duniya has initiated community engagement, like workshops, or the Playwrights Showcase?

Teesri Duniya regularly hosts panel discussions to raise relevant political issues and initiate a community dialogue. Our literary wing, alt.theatre magazine, provides a forum for artists, activists, academics and others to engage with issues of cultural plurality, politics and social activism to instigate an informed discussion of these topics.

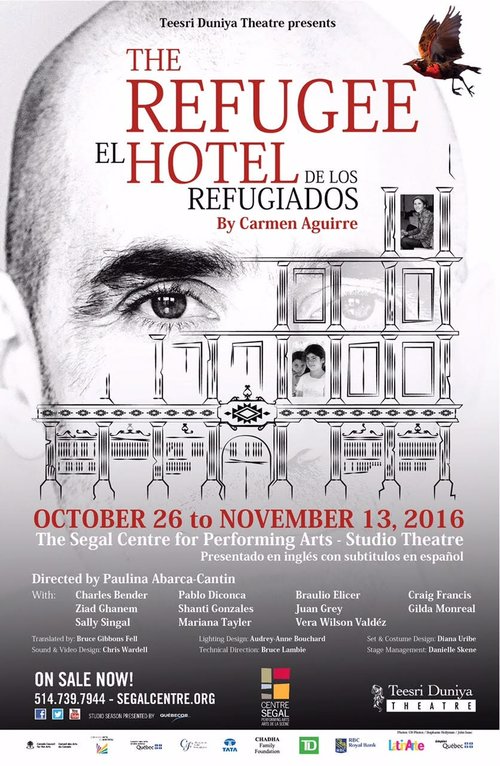

In 2016, we spearheaded a Welcome Refugees initiative, which sought to integrate newly arrived Syrians into Montreal’s community through theatre. We invited over 300 Syrians, as well as others who had arrived here as refugees, to our production of Carmen Aguirre’s The Refugee Hotel and conducted a series of panel discussions to open a meaningful dialogue on issues related to refugee displacement, resettlement, trauma and integration. This program was a manifestation of Teesri’s multicultural mandate; it transcended various linguistic barriers, engaging with audiences not only in English and French, but also Spanish and Arabic.

Apart from this, Teesri also conducts the Fireworks Beginners Playwright workshop on Sundays, which is aimed at helping emerging artists learn the basics of playwriting by developing a zero draft for a new play. In the same vein, we also have an artist-in-residence program that allows aspiring playwrights to work at Teesri and receive mentorship while developing their own plays.

What are some of the community spaces, organization or resources (networks, websites, journals) you might recommend for those interested in theatre and activism?

The Sambhavna Trust, the International Campaign for Justice in Bhopal, Concordia’s Center for Oral History and Digital Storytelling, and Montreal Storytelling are all organizations that do some great work at the intersection of theatre and activism. Teesri’s literary wing, alt.theatre is Canada’s only professional journal examining the intersections between politics, cultural plurality, social activism, and the stage, with a global outlook.

Speaking terms of representing cultural diversity, some notable organizations are the Black Theatre Workshop, Infinitheatre and Geordie Productions. Additionally, Montréal Arts Interculturels (MAI) continues to display the artistic as well cultural diversity of Montreal in ever newer ways, and Festival Accès Asie has become a landmark event in Montreal’s festival identity.

Through programming, community engagement, and organizational mandate, Teesri Duniya is situated at the intersection of theatre and political activism. What are some of the tangible ways in which you’ve seen theatre act as a catalyst for social change, or have a political impact?

Through programming, community engagement, and organizational mandate, Teesri Duniya is situated at the intersection of theatre and political activism. What are some of the tangible ways in which you’ve seen theatre act as a catalyst for social change, or have a political impact?

Theatre is not merely a means of representation, but it is also a means of redressal. Teesri has treated several social and political issues in its productions and makes it a point to organize post-play discussions to foster a dialogue that can catalyse real change. When we produced Birthmark, Corpus, and My Name is Rachel Corrie opposing communities side sat down side by side and discussed the controversial issues that separated them. With the production of Truth and Treason we engaged with issues raised by the war in Iraq and initiated a letter writing campaign for students, which entailed writing essays on war and peace. These inspired members of the community, primarily students, to start a petition to end of the war.

The beauty of theatre as a means of change is that artists can show the world not only how things are, but how things may be, depicting what is possible. Sartre believed theatre to be the most political of the arts because it provides the possibility of engagement in a very immediate way as compared to the arts. We have seen this manifest and that is why we continue to try and change the world, one play at a time.

What’s next for Teesri Duniya?

Teesri has several projects lined up for 2019-20. We will be producing Counter Offence, directed by Liz Valdez at the Segal Center. Following that we have Nadia Manzoor’s Burq Off!, directed by Tara Elliot, exploring intergenerational divides and the tension between tradition and freedom through the story of a young Pakistani woman. Honour: Confession of a Mumbai Courtesan, written and performed by Dipti Mehta, will be showcased at MAI. We will also be producing Beyond Sight by Audrey-Anne Bouchard, a play on disability; and lastly, we have a verbatim play by Jim Forsyth, chronicling the stories of Syrian refugees as they integrate in society, titled To Stand Again.

In addition to these productions, we will be publishing our quarterly magazine alt.theatre, and hosting an array of artist and community programs including a few lecture series, afterschool theatre instruction, and an initiative called Sharing our Lives, Telling our Stories directed by Deborah Forde.